|

Chapter

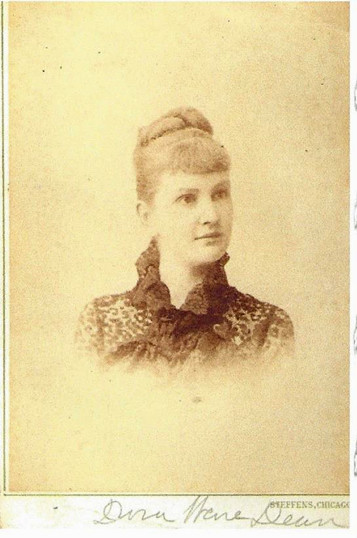

12 We know that Jane delivered her baby on August 10, 1864 – two days after the letter that James wrote. Eudora Murray Ware was born at Dickinson’s Bayou, near Galveston. By 1860, Dickinson had become a stop on the Galveston, Houston, and Henderson Railroad. It was (and is) located in Galveston County where Jane would often go to visit her uncle, Dr. William R. Smith. It may be for that reason that Jane was in Dickinson Bayou at the end of her pregnancy. It is also possible that she was attempting to travel to meet her seriously ill husband who was confined in bed. Either way, Eudora was not born in Galveston or Corpus Christi, but in this little area called Dickinson Bayou. Jane was 32 years old at her birth. Fanny Glassell, the firstborn child of James and Jane was five and brother, Somerville, was two. In an odd set of circumstances, the needed recovery of James allowed him to get a furlough to go home and see his new daughter.  Eudora

Murray Ware

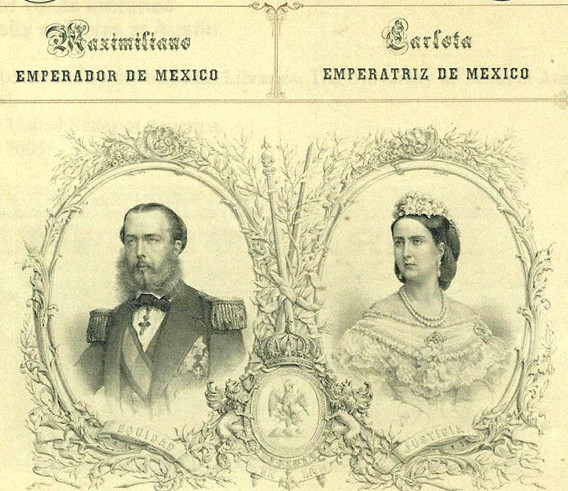

Photo owned by James and Judy Ware 197 In the fall of 1864, Col. Ford’s command was divided once again. As the old year drew to a close with James recovering physically, the new year of 1865 would find the Wares and all Southerners suffering from a different kind of ailment . . . the heartsick loss of land, security, lives, valuables, and a way of life that they would not see again. Their particular dream for the future would have to change dramatically in the coming months and years. They were clearly losing the war, and it seemed to be just a matter of time before the beleaguered southern soldiers could hold out no longer. Probably seeing the handwriting on the wall, James mustered out of the service on March 22, 1865. On April 9, 1865, a saddened but dignified General Robert E. Lee surrendered his army to General Ulysses Grant at a farmhouse in Appomattox.  The war was finally over, but the news did not reach all the far outposts in Texas until much later. In fact, the last official battle fought there “occurred at Palmito Hill in Texas on May 13, 1865, nearly five weeks after” the surrender. (Ref. 1008) Now the hard part really came for James and Jane . . . what to do now. As author Mathew Maury wrote, “Failed rebels traditionally faced one of two fates: flight into exile or hanging. American Confederates had another choice: returning to their homes and living in the restored country. Nearly all of them did — but not all.” (Ref. Mathew Maury) The year prior to the end of the war, in 1864, Napoleon III of France (entertaining global ambitions) had captured Mexico City and arranged for Maximilian, Archduke of Austria, to become Emperor of Mexico. His role of leadership was really only that of a puppet to France, but for a brief term he took control of much of the country. "Maximilian encouraged former Confederates to immigrate to his newly established empire by offering them generous 198

incentives.” (Ref. 3004) With news getting to Texas so much later than the rest of the country, James had no idea of what the terms of surrender or amnesty would be for him. So, along with thousands of other confederate soldiers, he decided to cross over into Mexico where “he was appointed Military Engineer in the Army of Maximilian.” (Ref. 830) He was in good company since so many of his friends and earlier commanders decided to do the same thing. “On June 26, 1865, “Shelby’s Brigade, Governors Reynolds and Allen, and Generals Smith and Magruder arrived at Eagle Pass. They crossed the Rio Grande into Mexico.” (Ref. 1008) Captain King went to Mexico too but returned after securing his pardon from President Andrew Johnson later in the year. Former Governor Pendleton Murrah and General Hamilton Bee crossed the border as well, and “on May 26, 1865, Ford moved his family to Matamoros” too. (Ref. 1008)  Maximilian and Carlota No one knew how long the exile would be for. Some soldiers returned home shortly, some found good work in Mexico to help send money home to desperate families (“the soldiers at Brownsville had not been paid for well more than a year.”), some brought their families with them, and some worked only until things could settle off and they could return safely to their home country. (Ref. 1008) 199

James ended up being “appointed Military Engineer in the Army of Maximilian." (Ref. 830) He did well at this job and it brought in much needed support for Jane, but it also required five years of separation. This was very common for many of the men as they readjusted to life after the war. Jane, with good reason, did not want to venture into Mexico with the young children, so she stayed closer to her parents and checked on their property in Corpus Christi. In 1870, when Texas was readmitted to the union, James and Jane were finally reunited back in Texas.  Scene from Mexico Photograph taken by Louis de Planque and owned by James & Judy C. Ware Just because the fighting was over, the next five years did not bring any sense of peace or calm to James or Jane. The new government, reeling after the assassination of President Lincoln, had the huge job of putting the country back together. Southerners had lost so much and were struggling to just survive, and Northerners were suddenly deluged with a population that desperately wanted freedom, but now had to find a way to earn a living. As a radical Republican, the post-war governor of Texas, E. J. Davis, took part in the constitutional conventions of 1866 and 1868-1869. As mentioned before, he was not a very popular politician in Texas, and he did little to soothe bitter feelings for the men who fought for the south. In 1867, there was “enacted the infamous reconstruction legislation putting the South under military rule. Texas was placed in the fifth military district with General Philip Sheridan as Commander. General Charles Griffin was put in 200

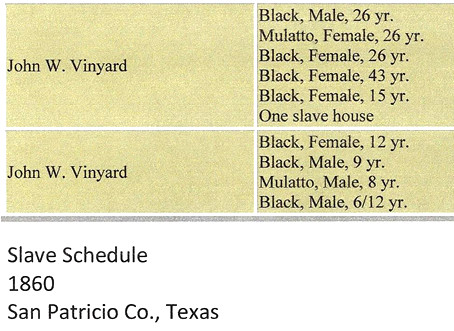

command of the State of Texas. The civil officers were permitted to remain in office only at the pleasure of the military. The Iron Clad Oath was prescribed as a qualification for voting and jury service. Few Southerners could take the oath conscientiously, which its designers well knew, and anticipated result was that the bulk of Southern manhood was disfranchised . . .” (Ref. 3296) Property settlements had to be disputed, old grievances were renewed, and with the confusion of the war, some new grievances arose out of unforeseen circumstances. Mr. J. W. Vineyard was a neighbor of the Wares before the war. According to history, the earliest community built up around that area in San Patricio was in 1854 when George C. Hatch purchased land on both sides of the bayou. He later acquired 3,800 acres of land which he sold to Walter Ingalls, Henry Nold, James A. Ware, John Pollard, John W. Vineyard and others. Mr. Vineyard was a wealthy man with several slaves (see slave schedule below) and clearly, from the following letter of James, they were in close enough proximity to run their herds together. In an effort to keep as much property as he could out of enemy hands, James had moved much of the cattle over to Mexico to safeguard them. Communication was almost impossible at this time in Texas, and Mr. Vineyard (only knowing that somehow much of his cattle ended up in Mexico) had no way of knowing that the action James took was actually in an effort to help him too. When Vineyard filed with the Court of Claims to find his cattle, James wrote them the letter (below) explaining the circumstances.  Slave Schedule for John W. Vineyard 201

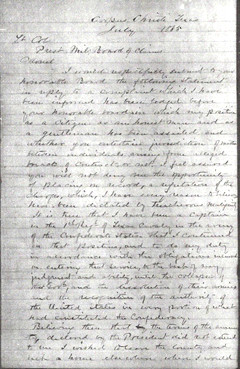

Original copy of letter written

by James in 1865

Corpus Christi, Texas July 1865 Lt. Col. President Board of Military Claims Colonel, I would respectfully submit to your honorable Board the following statement in reply to a complaint which I have been informed has been lodged before your honorable board in which my position as a citizen, as an honest man, and as a gentleman has been assailed and whether you entertain jurisdiction of matters between individuals arising from alleged breach of contracts or not, I feel assured you will not deny me the opportunity of placing on record, a refutation of the charges, which, I have every reason to believe have been dictated by treacherous malignity. It is true that I have been a captain in the 1st regiment of Texas Cavalry in the army of the Confederate States, that I continued in that position, and to do my duty in accordance with the obligations incurred on entering that service, to the best of my judgment and ability, until the collapse of that government and the dissolution of their armies and the recognition of the authority of the United States in every portion of what had constituted the Confederacy. Believing then that the terms of the amnesty declared by the President did not extend to me, I wished to leave the county and seek a home elsewhere where I would be free from the disabilities attaching to me in the United States.

202

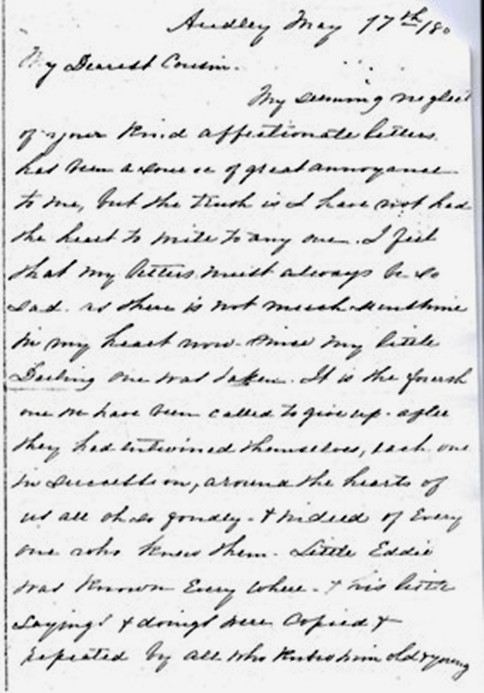

It is not true that I am indebted to Mr. J.W. Vineyard in the sense which he claims, or that I have ever desired to defraud him of what I justly owed him by the removal of stock, in which his claim was secured, to Mexico without his consent. It is true that I wished to remove a portion of my stock but as for my doing so to injure Mr. Vineyard’s interest, it was to protect that interest that I desired to do so as Mr. V. is one of the unfortunate persons who can only be restored to their civil rights by the special exercise of Executive clemency and that until that decency has been extended to him, I would be exceedingly unfair to make him (without a trial of our respective claims) the custodian of my entire property, subjecting it to serious loss and injury. I would respectfully submit that had I entertained any disposition to evade my obligations, I could have much more easily done so than by driving this stock from a distant country to the vicinity of Mr. V.’s residence and keeping them near him for weeks. Respectfully, James A. Ware (Ref. 3247) Fortunately, the misunderstanding was resolved. The five years after the end of the war were difficult for everyone, but it seemed as if a special cloud of sadness hung over the Ware family both in Texas and in Virginia. The year 1866 found James’ sister, Elizabeth Britton, still in deep mourning for the loss of her infant son, Josiah Ware Britton, and her husband who had died in November. Then on March 22, 1866, James’ little sister, Lucy Balmain Ware Lewis, lost another one of her children. She had already had to bury three other children, and her sadness was devastating. To lose a fourth child was almost too much to bear and yet, at the very time of his death, she was pregnant with (what would be) her last baby. One can feel the depth of her sorrow and worry in two letters that were written just shortly before she gave birth in August. On May 17, 1866, just two months after burying her fourth child, she wrote the following to a cousin: 203

“My seeming neglect of your kind affectionate letters has been a source of great annoyance to me, but the truth is I have not had the heart to write to anyone. I feel that my letters must always be so sad as there is not much sunshine in my heart now since my Darling one was taken. It is the fourth one we have been called to give up – after they had entwined themselves, each one in succession, around the hearts of us all, oh so fondly, and indeed of everyone who knew them. Little Eddy was known everywhere and his little sayings and doings were copied and repeated by all who knew him, old and young. I try to bear it all as well as I can for the sake of other loved ones around me. I find I must learn to kiss the rod that smites. “Thy will be done” and submission are two of the hardest tasks to be felt and learned in the school of affliction.” (Ref. 227)  Part

of the letter written by Lucy Ware Lewis after the death of baby

Eddy

original owned by James and Judy Ware 204

Then, in a letter to her sister, dated just one month before the birth of her last baby, it is almost as if Lucy sensed that her own death was imminent. She wrote the following: “You say if I never write again I will write now. Maybe there is more truth than you think in your remark – for God only knows what may be my fate within the next 4 or 6 weeks, as it is a trying time for me.”  (Ref. 15)

(The letter is very hard

to read because, due to the shortage of paper

in the Civil War, people would write in one direction and then turn the

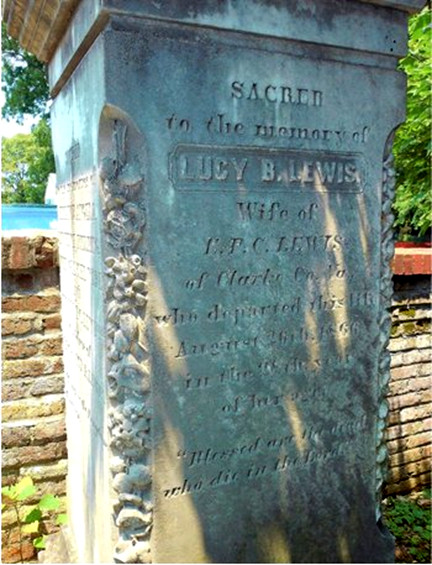

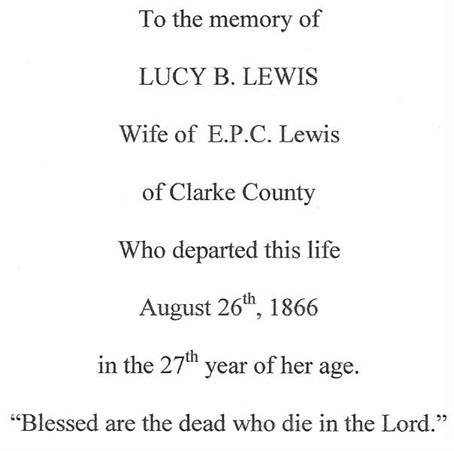

paper crosswise and write in the other direction.)Lucy’s uneasiness about the impending birth of her next child proved to be all too prophetic. A baby daughter was born on August 26, 1866, just three months after little Eddy was buried. The little girl was named Lucie Ware Lewis, in honor of her mother. This was the only child of Edward and Lucy’s who would survive childhood, marry, and have a family of her own. Tragically, her mother never got to witness it. Lucy died on August 26, 1866, at the birth of this last child. As mentioned earlier in this text, her sister, Elizabeth, stepped in to care for the new baby until poor Edward remarried a few years later. The entire family and community felt such grief over the fate of poor Lucy who was beloved by so many. There is a very special and appropriate place dedicated to Lucy within the walls of Grace Episcopal Church. A stained glass window adorns the lovely baptistry there and has witnessed generations of babies baptized into the church. The inscription plate reads: “To the glory of God and in memory of Lucy Balmain Lewis, wife of Edward Parke Custis Lewis and their four infant children” 205

A stained glass window was also

placed in Grace Episcopal Church in her

honor.

Photo taken by Judy C. Ware in 2002 206

The

following photographs were kindly taken by

Lee

McGuigan of Berryville, Virginia.

“Of

such is the Kingdom of Heaven”

Children of E. P. C. Lewis and Lucy Balmain Ware Lewis   Memorial lists the

following children for Lucy and Edward Parke Custis

Lewis:

Eleanor Angela, Lawrence Fielding, John Glassell Ware, and Edward P. C. Lewis, Jr. 207

Grave of

Lucy Balmain Ware Lewis

Both photos below are the property of James & Judy Ware.    Knowing how close James was to his younger sisters, he must have grieved greatly at the death of Lucy and the sorrow Elizabeth endured. 208

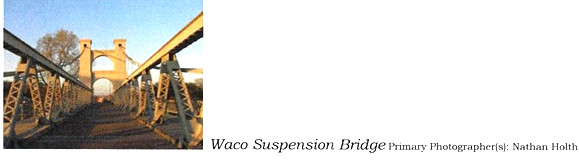

While James was in Mexico, Jane and the children stayed in Galveston most of this time, supporting her family by opening a school and teaching. Her years at Patapsco served her well. It was a blessing she was skilled in a profession that could pay money. Both Galveston and Corpus Christi suffered much after the war. Obviously, Confederate money meant nothing, and many soldiers in Texas had not been paid in months anyway, so there was nothing to send home to families.   Envelopes addressed to Jane or (Jennie) in both Corpus Christi and Galveston property of James and Judy Ware The dire circumstances and changes that abounded throughout all of Texas during these years after the war often played a part in the relocation of families. In 1866, the leading citizens of Waco, Texas (located between Austin and San Antonio) embarked on an ambitious project to build the first bridge to span the wide Brazos River. They formed the Waco Bridge Company to oversee the construction. The 475-foot brick Waco Suspension Bridge was called the longest span of any bridge west of the Mississippi River when completed in 1870. Since this bridge provided the only way to cross the

209

George and Julia Smith, with most of their family, decided to leave the coastal region of Texas and head toward this more central part of the state some time after the war. They eventually settled in Salado, Texas. Jane, at least for the time being, stayed close to Corpus, but she spent most of her time in Galveston with her Uncle William. She had already lost a sister, Milly, in 1861, and in 1862, her brother Rueben died of complications of disease while serving with his unit during the war. From the time of the surrender until 1870, life for Jane was a day-to-day struggle to raise her children, teach in Galveston, and try to provide food and necessities on the little money that her husband could earn in Mexico and send to her. James, meanwhile, was hard at work learning the trade of civil engineering in Maximilian’s army. (Ref. 830) According to an excerpt from his obituary, “He became an expert civil engineer and doubtless could have attained a name and fame in that direction - had he desired to pursue it as a life profession.” (Ref. Obituary) The hope for a reunion for the Wares and a more secure life began with the 1869 gubernatorial election which was one of the most turbulent and controversial in Texas history. In 1867, General Philip Sheridan, who was the military head of the Reconstruction government, appointed Elisha Pease as the civilian governor of Texas. Pease “needed (since he ruled by order of Congress and the Army and against the will of the people) to impose a provisional government on Texas, with the result that civilian control waned. Pease urged the Constitutional Convention of 1868-1869 to accept radical reconstruction so that Texas could normalize relations with the Union as soon as possible.” As a radical Republican, E. J. Davis took part in the constitutional conventions of 1866- 69, but Pease supported A. J. Hamilton in the gubernatorial race of 1869. Davis ended up winning the election and “in 1870, Pease joined A. J. Hamilton and James Throckmorton in protesting the conduct of the Davis administration.”(Ref. War, Ruin, and Reconstruction by Edward Clark) Davis was determined to make Texas pay for its’ disloyalty to the union. Despite his resentment, however, one huge event happened during his administration. The state of Texas was readmitted to the union on March 30, 1870. 210

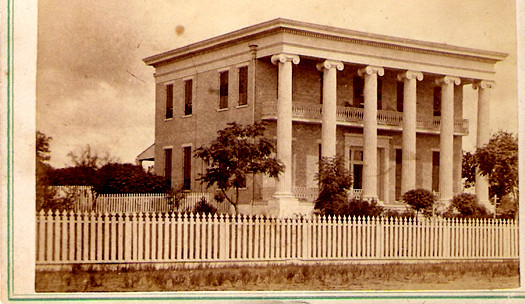

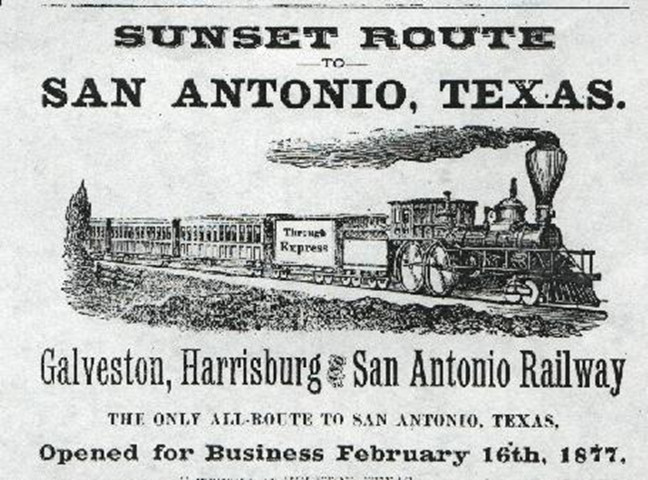

Photo of the Governor’s Mansion in Austin given to Elizabeth Ware Britton by her sister-in-law, Mrs. Davis It is now owned by James and Judy Ware. With the inclusion of Texas back in the Union, James could now return to his homeland and reunite with Jane. The major hurdle, or course, was to find a job. Jane’s uncle, Dr. William R. Smith, would prove to be a big help in this matter. Dr. Smith, who had served twice as United States Collector of Customs in Galveston, was also credited with the advancement of the early railroad in the area. One of his business associates was Thomas Wentworth Peirce, a wealthy railroad tycoon in the 1800s. Peirce was from Massachusetts and, therefore, did not have the stigma attached to him that southern businessmen did. He had continued to gain more wealth during the war. He owned a large sugar plantation at Arcola served by the Houston Tap and Brazoria Railroad and was one of a group of investors, including Jonathan Barrett of Boston and John Sealy of Galveston, who purchased the bankrupt road in January 1870. They immediately petitioned the legislature for a new charter, which was granted that year under the name Galveston, Harrisburg and San Antonio Railway Company.  Thomas Wentworth Peirce

There were five persons in the new company holding interests, but when Mr. Sealy later sold out, Mr. Peirce ultimately became the sole owner with the exception of 211

a few shares issued for construction purposes. Jane turned to this old friend of the family and business associate of her uncle in hopes of finding a job for James. From the letters exchanged during this time period, he was obviously able to find a position for the exiled Captain Ware. Unfortunately, it was not an ideal situation because his job would require that James travel a great deal on surveying expeditions, so there were still times he and Jane could not be together. In a time when southerners were scrambling for employment of any kind, however, it was a Godsend. James was able to use his newly honed experience as a civil engineer on an American railroad, provide an income (albeit small) for his family, and get one step closer to his real passion of working in law. Most importantly, it allowed James and Jane both to look forward and finally see a future together without war and bloodshed being a constant companion.  212 |

|

This site maintained by John Reagan |